7. BHSA Components and Requirements

A. Behavioral Health Services and Supports

A.1 Behavioral Health Services and Supports Expenditure Guidelines

Counties are required to allocate 35 percent of their total local Behavioral Health Services Act (BHSA) allocations for Behavioral Health Services and Supports (BHSS).[1] BHSS categories include:

Children’s, Adult, and Older Adult Systems of Care

Outreach and Engagement

Workforce Education and Training

Capital Facilities and Technological Needs

Early Intervention Programs

Innovative Behavioral Health Pilots and Projects

Of the 35 percent of funds allocated to BHSS, counties are required to use 51 percent of funds for Early Intervention Programs, and of that, 51 percent of the funds for Early Intervention Programs must be used to serve BHSA eligible individuals who are 25 years of age and younger. Counties may, but are not required to, fund BHSS categories other than Early Intervention. Counties will be required to report on the amount of BHSS funds, planned expenditures in the Integrated Plan and actual expenditures in the Behavioral Health Outcomes, Accountability, and Transparency Report (BHOATR), apportioned to each BHSS category they choose to fund. Additional information on county allocation requirements can be found in Chapter 6, Section B.1.

Counties may include Innovative Behavioral Health Pilots and Projects across all BHSS categories. Additional information on Innovative Behavioral Health Pilots and Projects can be found below in Chapter 7, Section A.6.

Counties should maximize the use of other available sources of funding, including Medi- Cal, to provide BHSS services. However, counties are not required to exhaust these other funding sources before using BHSS funds. Additional information on requirements to maximize non-BHSA sources of funding can be found in Chapter 6, Section C.

Counties may use shared resources to advance multi-county BHSS projects. Each county will be expected to report on multi-county projects in their respective Integrated Plan.

A.2 Children’s, Adult, and Older Adult Systems of Care

Counties may use a portion of BHSS funds to provide Children’s, Adult, and Older Adult Systems of Care services, including substance use disorder services, to BHSA eligible and priority populations. System of care services are those pursuant to Part 4 for the Children’s System of Care and Part 3 for the Adult and Older Adult System of Care.[2] Additional information on BHSA eligible and priority populations can be found in Chapter 2, Section B.3.

Children’s, Adult, and Older Adult Systems of Care services funded under BHSS may not include Housing Interventions or services for individuals enrolled in a Full Service Partnership (FSP). Housing Interventions and FSP services should be funded under those components.

A.3 Outreach and Engagement

Counties may use a portion of BHSS funds for Outreach and Engagement (O&E). BHSS funds may be used for activities intended to reach, identify, and engage individuals, families, and communities in the behavioral health system and reduce disparities.

Counties may include evidence-based practices and community-defined evidence practices in the provision of activities.[3]

BHSS O&E activities involve broad engagement of unserved and underserved populations in the behavioral health system. These activities are distinct from those that may be funded as part of BHSS Early Intervention Programs, Housing Interventions, or FSP programs. County Early Intervention programs must include an outreach component, and counties may use FSP funding for outreach activities to enroll individuals in an FSP. Additionally, counties may utilize up to 7 percent of their Housing Intervention funds on identified Outreach and Engagement activities. O&E activities that are required as a part of as part of BHSS Early Intervention programs or FSP should be funded and tracked in county Integrated Plans (IPs) and BHOATRs as part of those programs, rather than under the BHSS O&E category. Additional information on BHSS Early Intervention can be found in Chapter 7, Section A.7 and additional information on FSPs can be found in Chapter 7, Section B.

BHSS funds may be used for O&E activities to engage individuals in housing interventions, if the county is not funding these activities under Housing Interventions . For example, BHSS funds may be used to conduct outreach to individuals in encampments to support connection to housing programs. Additional information on allowable uses of Housing Intervention funds can be found in Chapter 7, Section C.

When the county works in collaboration with other non-behavioral health community programs and/or services, only the costs directly associated with outreach and engagement activities to provide mental health and substance use treatment can be funded under the BHSS O&E category.

Examples of O&E activities that may be supported with BHSS funds include but are not limited to:

Outreach to and collaboration with individuals and entities that can help reach, identify, and engage individuals and communities in the behavioral health system, which may include but are not limited to:

Community-based organizations

Housing Agencies

Street medicine/field-based service providers

Harm reduction/syringe services programs

Community leaders

Schools

Early Care and Learning

Tribal communities

Primary care providers

Senior centers

Senior Housing (including affordable senior housing and other types of retirement communities, local Area Agencies on Aging, and the local Aging and Disability Resource Connections)

Hospitals (including emergency departments and behavioral health urgent care)

Federally Qualified Health Centers

Faith-based organizations

Outreach to directly reach and engage individuals who may benefit from behavioral health services and engagement to support and encourage ongoing participation of the eligible population in behavioral health treatment, such as:

Peer Support Services[4] including resource navigation.

Enhanced Community Health Worker services[5] under Behavioral Health Community-Based Organized Networks of Equitable Care and Treatment (BH-CONNECT), which include health navigation, health education, support and advocacy, and tailored preventive services for Medi-Cal members living with significant behavioral health needs.

Food, clothing, and other basic necessities, when the purpose is to engage unserved individuals and, when appropriate, their families in the behavioral health system. These services should support the ability to provide for the immediate needs of an individual.

Strategies to reduce ethnic, racial, gender-based, age-based, or other disparities, such as:

Engaging individuals, families, and credible messengers from priority communities to design and provide input on outreach strategies and messages so that they meet the unique needs of those populations.

Outreach to individuals through community sites that are natural gathering places for priority populations.

A.4 Workforce Education and Training

Counties may use a portion of BHSS funds for Workforce Education and Training (WET). County-operated and/or county-contracted providers that are employed or volunteer in the county behavioral health delivery system may participate in WET activities.

Counties should incorporate efforts to increase the racial, ethnic, and geographic diversity of the behavioral health workforce, including incorporating individuals with lived experience into the workforce, across all WET activities. BHSS funds for WET activities must be spent within ten years, after which unspent funds will be subject to reversion. All transfers into WET are irrevocable and cannot be transferred out of WET. Additional information on fiscal policies can be found in Chapter 6, Sections B.7 and B.8.

A.4.1 WET Alignment with Statewide Workforce Initiatives

WET activities must supplement, but not duplicate, funding available through other state-administered workforce initiatives, including the Behavioral Health Community-Based Organized Networks of Equitable Care and Treatment (BH-CONNECT) workforce initiative administered by the Department of Health Care Access and Information (HCAI). Counties must prioritize available BH-CONNECT and other state-administered workforce programs whenever possible.

BHSS funds must be used to:

Supplement workforce activities funded through BH-CONNECT and other state- administered programs (e.g., stipends for childcare or transportation to supplement a retention bonus available through the BH-CONNECT workforce initiative).

Create WET programs within the county that complement state-administered workforce programs.

A.4.2 WET Allowable Activities

WET activities must only address the needs of the county behavioral health delivery system. Activities that may be supported with BHSS funds include, but are not limited to, the following[6]:

Workforce recruitment, development, training, and retention

Professional licensing and/or certification testing and fees

Loan repayment

Retention incentives and stipends

Internship and apprenticeship programs

Continuing education

Efforts to increase the racial, ethnic, and geographic diversity of the behavioral health workforce (e.g., individuals with lived experience)

Staff time spent supervising interns and/or residents who are providing direct county behavioral health services through an internship or residency program.

BHSS funds for WET activities may not be used to:

Address the workforce recruitment and retention needs of systems other than the county behavioral health delivery system, such as criminal justice, social services, and other non-behavioral health systems, although county behavioral health may choose to partner with other systems in order to meet the intersecting needs of its clients.

Pay for staff time spent providing direct behavioral health services.

Employers must not be reimbursed for the time an employee takes from their duties to attend training.

Off-set lost revenues that would have been generated by staff who participate in WET programs and/or activities.

Counties may also use BHSS funds to support administration and coordination of all WET programs and activities (e.g., hiring a WET coordinator).

County-operated and/or county-contracted providers that are employed or volunteer in the county behavioral health delivery system may participate in WET activities. Certain WET activities require a commitment to employment in the county behavioral health delivery system over a certain time. Additional information on WET activities is provided in subsequent sections (Chapter 7, Sections A.4.3 – A.4.9).

A.4.3 Workforce Recruitment, Development, Training, and Retention

Counties may use BHSS funds for county-operated and county-contracted behavioral health workforce recruitment, development, training, and retention activities that include the following:

Recruitment and Retention

Recruitment and retention activities may include, but are not limited to, the following:

Supporting workforce recruitment, including recruiting culturally and linguistically competent staff.

Providing financial incentives to recruit or retain employees.

Providing supported employment services to employees and individuals seeking employment.

Creating and implementing promotional opportunities and policies that promote job retention.

Establishing Regional Partnerships to support recruitment and retention.

Providing wellness activities that promote retention and decrease burnout.

Training and Technical Assistance

Training and technical assistance activities may include, but are not limited to, the following:

Education and training programs and activities for prospective and current employees, contractors, and volunteers.

Collaboration and partnerships to develop curricula and provide training to groups such as individuals receiving services and their family members; individuals from underrepresented racial/ethnic, cultural, and linguistic communities; and other unserved or underserved communities.

Activities that incorporate the input of individuals receiving services and their family members and, whenever possible, utilize them as trainers and consultants in WET programs and/or activities.

Activities that promote cultural and linguistic competence and incorporate the input of diverse racial/ethnic populations that reflect California's general population into WET programs and/or activities.

Payment to trainers for training, technical assistance, and consulting, and travel expenses of trainers and participants, including mileage, lodging, and per diem.

Other costs of providing training, such as materials, supplies, and room and equipment rental costs; also staffing support around administrative tasks, such as paperwork and billing.

Evaluation of the effectiveness of the training and its impact on service delivery.

Employees, contractors and volunteers in non-behavioral health systems, such as criminal justice, social services and health care may participate in training and technical assistance programs and activities; however, they cannot be the sole recipients.

Behavioral Health Career Pathway Programs

Behavioral health career pathway activities may include, but are not limited to, the following:

Programs to prepare individuals receiving services and/or their family members for employment and/or volunteer work.

Programs and coursework in high schools, adult education, regional occupational programs, colleges, and universities that introduce individuals to and prepare them for employment.

Career counseling, training, placement programs, and/or outreach that increase access to employment to unserved and underserved groups and individuals who share the racial/ethnic, cultural, and/or linguistic characteristics of individuals receiving services, their family members, and others in the community with behavioral health needs.

Supervision of employees that are in a Behavioral Health Career Pathway Program.

Workforce Staffing Support

Workforce staffing support may include, but are not limited to, the following activities:

Staff to plan, recruit, coordinate, administer, support, and/or evaluate WET programs and activities when the staff is not funded through any of the other funding components.

Staff to support Regional Partnerships[7] when performing activities that address the following:

Shortages within the workforce or shortages of workforce skills identified as critical by the Regional Partnership.

Deficits in cultural and/or linguistic competence.

Promotion of employment and career opportunities for individuals receiving services and their family members.

Staff to provide ongoing employment and educational counseling and support to individuals receiving services and/or their family members who are entering or currently employed in the workforce.

Staff to provide education and support to employers and employees to assist with the integration of individuals receiving services and/or their family members into the workforce.

A.4.4 Professional Licensing and/or Certification Testing and Fees

Counties may use BHSS funds to cover fees associated with preparing for, applying for, or renewing a license or certification for individuals who are employed, on a full- or part-time basis, in the county behavioral health delivery system.

Counties may support a wide range of activities related to licensing and certification including, but not limited to:

Any fees associated with preparing for, applying for, or renewing a license or certification, such as:

Academic membership fees

Application fees, including fees to obtain academic transcripts or have photos taken of the applicant

Exam fees

Background check fees

License renewal fees

Board of Behavioral Sciences (BBS) registration fees

Fees associated with transferring a license or certification from another state to California

Transportation fees associated with preparing for, applying for, or renewing a license or certification

Any activities that enable provider testing for a license or certification, such as training courses, costs of study material, or coaching.

A.4.5 Loan Repayment

Counties may use BHSS funds to establish locally administered loan repayment programs that pay a portion of the educational loans of individuals who make a commitment to work in the county behavioral health delivery system. Counties have the flexibility to establish loan repayment programs that meet local needs but must adhere to the following minimum requirements.

Eligible Educational Loans

Only loans held by an educational lending institution are eligible for assumption. Eligible educational loan programs include but are not limited to:

The Federal Family Education Loan Program in 20 U.S.C. Sec. 1071 et seq.

The Federal Direct Loan Program in 20 U.S.C. Sec. 1087b et seq.

The following fiscal liabilities are not eligible for loan assumption:

An educational loan(s) that has not been disbursed at the time the applicant signs a loan assumption application and a loan assumption agreement

An educational loan that was used for the educational expenses of someone other than the applicant

An educational loan that has been consolidated with a loan of another person or with a non-educational loan

Lines of credit

Home equity loans

Credit card debt

Business loans

Mortgages

Personal loans

Other consumer loans

Eligible Participants and Service Providers

Individuals must be employed on a full- or part-time basis and must commit to a county-determined term of employment. Counties must ensure terms of employment are met and establish processes to recoup funds should recipients not meet their service commitments, when appropriate.

Maximum Repayment Amount

Loan repayment will be subject to the maximum repayment amounts in alignment with the BH-CONNECT workforce initiative:

There is no lifetime limit on loan repayment amount.

Up to $240,000 per licensed practitioner with prescribing privileges and individuals in training to be a licensed practitioner with prescribing privileges, including but not limited to: Psychiatrists, Addiction Medicine Physicians, and Psychiatric Mental Health Nurse Practitioners.

Up to $180,000 per non-prescribing licensed or associate level pre-licensure practitioner, including but not limited to: Psychologists, Clinical Social Workers, Professional Clinical Counselors, Marriage and Family Therapists; Occupational Therapists, and Psychiatric Technicians

Up to $120,000 per Alcohol or Other Drug Counselors, Community Health Workers, Peer Support Specialists, Wellness Coaches, and other non-prescribing practitioners meeting the provider qualifications for Community Health Worker services, Rehabilitative Mental Health Services, Substance Use Disorder Treatment Services, and Expanded Substance Use Disorder Treatment Services in the California Medicaid State Plan.

Service Obligation

Counties have the flexibility to define service obligations for participants that are commensurate with the loan repayment amount for up to two years for each year of loan repayment. Counties must ensure service obligations are met and have processes to recoup funds if commitments are not met.

Payments

Payments must be made directly to the lending institution and must be applied to the principal balance, if not otherwise prohibited by law or by the terms of the loan agreement between the participant and the educational lending institution.

A.4.6 Retention Incentives and Stipends

Retention incentives and stipends pay or reimburse individuals directly for expenses, or a portion of the expenses, associated with employment or participation in training, educational programs, or other activities in preparation for working in the county behavioral health delivery system. Employment must be on a full- or part-time basis, and recipients must commit to a county-determined term of employment that is commensurate with the incentive or stipend amount. Counties must ensure that the terms of employment are met and must establish processes to recoup funds should recipients not meet their service commitments.

The county may contract with a fiduciary entity, university, or accredited educational institution to establish incentive and stipend programs.

Counties have the flexibility to define which expenses are eligible for retention incentives and stipends and the level of payment. Examples of these types of incentives and stipends include:

Scholarships, which may include, but are not limited to:

Tuition

Registration fees

Books and supplies

Room and board

Childcare

Eldercare

Transportation

Other costs and fees associated with attending an educational program

Recruitment bonuses and retention bonuses, which may include, but are not limited to:

Signing bonuses

Performance bonuses

Spot bonuses

Referral bonuses

Retention incentives and stipends, which may include, but are not limited to:

Travel expenses including commuting to work and mileage, lodging and per diem if travel is for the purpose of participating in an educational or training activity or for professional travel

Home office costs

Professional insurance

Childcare

Eldercare

Wellness

Moving or relocation expenses

Housing

Cellphone or internet services to support employment

Training and professional development costs

As described above, county BHSS funds should supplement activities funded through the BH-CONNECT or other state-administered workforce initiative. Use of BHSS funds to supplement BH-CONNECT programs may be particularly beneficial in scenarios where certain costs are not allowable as part of the BH-CONNECT workforce program. For example, counties may use BHSS funds for stipends for childcare, housing, or other wraparound supports as an “add-on” to a recruitment or retention bonus available through BH-CONNECT.

A.4.7 Internship and Apprenticeship Programs

Counties may use BHSS funds for internship and apprenticeship programs. For activities that involve supervision of post-graduate interns, only faculty time spent supervising interns in programs designed to lead to licensure or certification may be funded.

Activities and expenses that may be funded as part of residency and internship programs include but are not limited to:

Time required of staff, including university faculty, to supervise psychiatric residents or post-graduate interns training to work as psychiatric nurse practitioners; masters of social work; marriage and family therapists; clinical psychologists; clinical counselors; licensed marriage and family therapists; or certified addiction treatment, substance use disorder, or alcohol and other drug counselors.

Time required of staff, including university faculty, to train psychiatric technicians or to train physician assistants to work in the county behavioral health delivery system and to prescribe psychotropic medications under the supervision of a physician.

Addition of a mental health specialty to a physician assistant program.

A.4.8 Continuing Education

Counties may support a wide range of activities related to continuing education in order to develop and retain a well-trained behavioral health workforce, including:

Costs associated with both virtual and in-person continuing education opportunities, including:

Registration fees.

Development and preparation for continuing education, including expenses and consulting fees.

Payment to trainers.

Other costs of providing continuing education, such as materials, supplies, and room and equipment rental costs.

Travel expenses of trainers and county behavioral health delivery system participants, including mileage, lodging and per diem.

Costs associated with purchasing or renewing online training systems or platforms that offer continuing education courses.

A.4.9 Efforts to Increase the Racial, Ethnic, and Geographic Diversity of the Behavioral Health Workforce

Counties may use BHSS funds for activities to increase the racial, ethnic, and geographic diversity of the behavioral health workforce, including incorporating individuals with lived experience into the workforce. Efforts to diversify the workforce should be incorporated across WET activities in recognition of the need to develop a culturally and linguistically competent workforce that can meet the behavioral health needs of individuals of all backgrounds.

A.5 Capital Facilities and Technological Needs

Counties may use a portion of BHSS funds for Capital Facilities and Technological Needs (CFTN). BHSS CFTN projects include the acquisition and development of land, the construction or renovation of buildings, or the development, maintenance, or improvement of information technology to support behavioral health administration and services. Counties can also use BHSS funds as the required match for Behavioral Health Infrastructure Bond Act of 2023 Behavioral Health Continuum Infrastructure Program (BHCIP) awards. BHSS funds for CFTN projects must be spent within ten years, after which unspent funds will be subject to reversion. All transfers into CFTN are irrevocable and cannot be transferred out of CFTN. Additional information on fiscal policies can be found in Chapter 6, Sections B.7 and B.8.

A.5.1 Capital Facilities

BHSS funds may be used by counties for capital facility expenditures. Funds may be used to acquire, develop, or renovate buildings or to purchase land in anticipation of acquiring/constructing a building. Capital facility activities do not include Housing Interventions.

Capital facilities funds must be used for land and buildings, including administrative offices, that support behavioral health administration and services and enable the county to meet objectives outlined in its Integrated Plan. BHSS funds may be used by counties for capital facility expenditures for county owned and county contracted providers providing behavioral health services to the county. Specific allowable uses include:

Acquiring and building upon land that will be county-owned.

Acquiring, constructing, or renovating buildings that are or will be county-owned (e.g., residential care/treatment facilities, clinics, clubhouses, wellness and recovery centers, office spaces, or buildings where behavioral health vocational, educational, and recreational services are provided). The building can be owned and operated by a non-profit if the non-profit is providing behavioral health services under contract with the county.

Establishing a capitalized repair/replacement reserve for buildings, including administrative offices, that enable the county to meet objectives outlined in its Integrated Plan and/or personnel costs directly associated with a capital facilities project.

Renovating buildings that are county or privately owned if the building is dedicated and used to provide county behavioral health services.

Acquiring facilities not secured to a foundation that is permanently affixed to the ground (e.g., vehicles that provide mobile medication for opioid use disorder services, modular buildings for behavioral health services located on school grounds). Acquisition of these facility types is permissible for both the county and for non-profit behavioral health providers.

Meeting the match requirements for Behavioral Health Infrastructure Bond Act of 2023 BHCIP awards (Bond BHCIP). Capital facilities funds used as a match for Bond BHCIP awards must meet all Bond BHCIP requirements. The use of BHSA funds for BHCIP match requirements is permissible for both the county and for non-profit behavioral health providers.

The following additional requirements apply to capital facilities projects:

BHSS funds for capital facilities can only be used for those portions of land and buildings where county behavioral health services are provided.

Land acquired and built upon or construction/renovation of buildings using BHSS funds must be used to provide county behavioral health services for a minimum of twenty years.

All buildings under this component must comply with federal, state, and local laws and regulations, including zoning and building codes and requirements; licensing requirements, where applicable; fire safety requirements; environmental reporting and requirements; hazardous materials requirements; the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), California Government Code Section 11135, and other applicable requirements.

Capitalized repair/replacement reserves must be controlled, managed, and disbursed by the county.

Counties may “lease (rent) to own” a building if “lease (rent) to own” is preferable to the outright purchase of the building and the purchase of such property, with BHSS funds, is not feasible. Counties must provide information on why the purchase of the property is not feasible in their Integrated Plan.

County Behavioral Health Departments may purchase land with BHSS funds even if they do not plan to use BHSS funds for the construction of a building or purchase of a building (e.g. modular, etc.) if they have other expected sources of income for the planned construction or purchase of a building upon this land and the purchase serves to increase the county’s infrastructure. The purchase must serve to increase the county’s infrastructure for behavioral health services. Counties must include an explanation of the timeline and expected sources of income for the land in their Integrated Plan.

Examples of costs for which BHSS funds may not be used for capital facilities activities include:

Facilities where the purpose of the building is to provide housing.

Master leasing or renting of building space.

Purchase of vacant land with no plan for building construction.

Acquisition of land and/or buildings and/or construction of buildings, and establishment of a capitalized repair/replacement reserve when the owner of record is a nongovernment entity.

Operating costs for the building (e.g., insurance, security guard, taxes, utilities, landscape maintenance, etc.).

Furniture or fixtures not attached to the building (e.g., desks, chairs, tables, sofas, lamps, etc.).

A.5.2 Technological Needs

BHSS funds may be used to 1) increase individual and family empowerment and engagement by providing the tools for secure access to their health information and 2) modernize and transform clinical and administrative information systems. Counties may combine their resources to advance multi-county technological needs projects.

BHSS funds may be used for technological needs expenditures that support behavioral health administration and services including, but not limited to, the following:

Electronic health record (EHR) system projects including but not limited to:

Infrastructure, security, privacy

Practice management

Clinical data management

Computerized provider order entry

Full EHR with interoperability components (for example, standard data exchanges with other counties, contract providers, labs, pharmacies)

Individual and family empowerment projects including but not limited to:

Individual/family access to computing resources projects

Personal health record system projects

Online information resource projects (expansion/leveraging information sharing services)

Other technological needs projects and expenditures that support behavioral health operations including but not limited to:

Telemedicine and other rural/underserved service access methods

Pilot projects to monitor new programs and service outcome improvement

Data warehousing projects/decision support

Imaging/paper conversion projects

Multi-county technological needs projects

Maintenance costs, such as subscriptions to maintain EHRs or other systems

Resources to support compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Title II requirements for web content and mobile app accessibility, California Government Code Section 11135 and other applicable requirements.

A.6 Innovative Behavioral Health Pilots and Projects

The goal of innovative behavioral health pilots and projects is to build the evidence base for the effectiveness of new statewide strategies. Counties are encouraged to pilot and test innovative behavioral health pilots and projects in all BHSA funding components (Housing Interventions, FSP, and BHSS).[8] Counties should fund innovative behavioral health pilots and projects under each of those separate funding components.

A.7 Early Intervention Programs

Under the Mental Health Services Act, Prevention and Early Intervention made up one of the five program components. Now, Early Intervention is covered under BHSS to be provided by counties and four percent of total BHSA funding will be used by the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) for statewide Population-Based Prevention programs and activities.

Under BHSA, each county must establish and administer an Early Intervention program that is designed to prevent mental illnesses and substance use disorders from becoming severe and disabling and to reduce disparities in behavioral health.[9] At least 51 percent of BHSS funding must be used to fund Early Intervention programs and services. At least 51 percent of the BHSS Early Intervention funding must be used to serve eligible individuals who are 25 years of age and younger, including transitional aged youth.[10] Early Intervention funds may also be used to provide supports and services to parents and caregivers. However, these services do not count toward the 51% requirement spent on individuals who are 25 years and younger. Early Intervention funds can also be used to support innovative behavioral health pilots and projects within these parameters to build the evidence base for the effectiveness of new statewide strategies.[11]

County Early Intervention programs must also include a Coordinated Specialty Care for First Episode Psychosis (CSC for FEP) program beginning July 2026. More information on CSC-FEP requirements can be found in Chapter 7, Section A.7.5.

County Early Intervention programs must emphasize the reduction of the likelihood of the following adverse outcomes for BHSA eligible individuals:[12]

Suicide and self-harm

Incarcerations

School suspension, expulsion, referral to an alternative or community school, or failure to complete (inclusive of early childhood zero to five years of age, Transitional Kindergarten (TK)-12, and higher education)

Unemployment

Prolonged suffering

Homelessness

Removal of children from their homes

Overdose

Mental illness in children and youth through social, emotional, developmental, and behavioral services and supports in early childhood

Culturally Responsive and Linguistically Appropriate Interventions

County Early Intervention programs must include culturally responsive and linguistically appropriate interventions. These interventions must be able to reach underserved cultural populations[13] and address specific barriers related to racial, ethnic, cultural, language, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, religion, age, economic, or other disparities in mental health and substance use disorder treatment services access, quality, and outcomes.[14]

County Early Intervention programs must create critical linkages with community-based organizations, including, but not limited to, service and treatment providers, youth centers, licensed and exempt clinics, facilities and providers licensed or certified by the DHCS, licensed or certified residential substance use disorder facilities, and licensed narcotic treatment programs. Community-based organizations may also include organizations that provide evidence-based practices (EBPs) or community-defined evidence practices (CDEPs).[15]

Counties are encouraged to partner with community-based organizations that specialize in serving specific populations that are underserved and address specific barriers in the above paragraphs. DHCS encourages the use of CDEPs at the local level to address historical behavioral health disparities. CDEPs are an alternative or complement to EBPs, that offer culturally anchored interventions that reflect the values, histories and life experiences of the communities that the provider is providing services. These practices come from the community and the organizations that serve them and are found to yield positive results as determined by community consensus over time.

A.7.1 Early Intervention

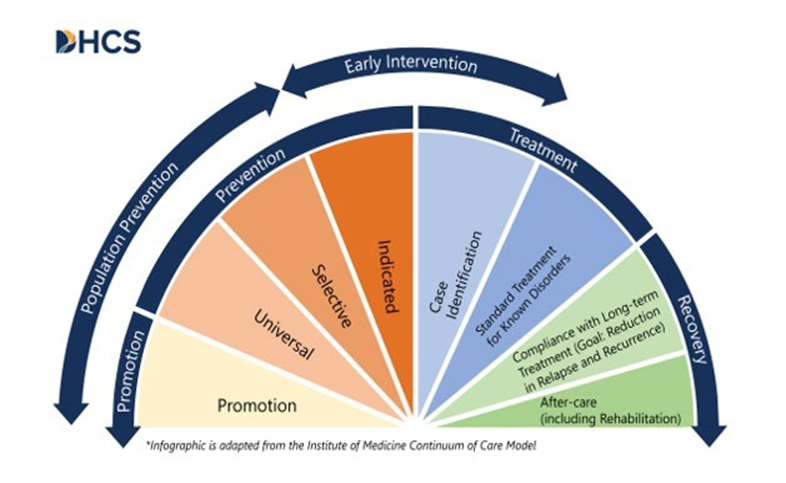

Early Intervention is the proactive approach of identifying and addressing behavioral health concerns in their early stages before they escalate into more severe, disabling or chronic conditions. DHCS has adapted the Institute of Medicine’s Continuum of Care to clarify the types of behavioral health services and supports that can be funded under BHSS Early Intervention programs.[16]

Under the Institute of Medicine’s Continuum of Care model, there is a spectrum that spans prevention and early intervention, and within the spectrum, there are differentiations based on type of intervention.

Figure 7.A.1. The Institute of Medicine’s Continuum of Care and Spectrum of Early Intervention Services

Under this model, Early Intervention must focus on strategies and activities that are directed to an eligible individual, including indicated prevention and case identification.

Early Intervention services may be provided to individuals lacking a specific diagnosis. Indicated prevention interventions focus on BHSA eligible at-risk individuals who are at risk or and experiencing early signs of a mental health or substance use disorder or who have experienced known risk factors for poor behavioral health outcomes, such as trauma, Adverse Childhood Experiences, or involvement with child welfare or corrections system. This at-risk individual may not yet meet the criteria of a diagnosable mental health or substance use disorder. Indicated prevention is the only prevention intervention that is allowable under Early Intervention, as shown in Figure 7.A.1. Examples of indicated interventions include, but are not limited to, outreach, training, and education for high-risk individuals and/or families who are at risk and experiencing early signs of a mental health or substance use disorder. Indicated interventions are preventive and often provided before an individual receives or meets diagnostic criteria for a behavioral health diagnosis. Case identification includes assessment, diagnoses, brief interventions, and activities needed to create access and linkages to care that connect individuals to the appropriate care.

County Early Intervention programs target BHSA priority populations and have the goal of identifying these individuals for access and linkage to services and treatment as needed. Additional information on BHSA eligible and priority populations can be found in Chapter 2, Section B.3.

A.7.2 Priorities for Use of Funds

County Early Intervention programs must focus on the following priorities[17]:

Childhood trauma early intervention to deal with the early origins of mental health and substance use disorder treatment needs, including strategies focused on:

Eligible children and youth experiencing homelessness.

Justice-involved children and youth.

Child welfare-involved children and youth with a history of trauma.

Other populations at risk of developing a mental health disorder or condition as specified in subdivision (d) of WIC 14184.402 or substance use disorders.

Eligible children and youth in populations with identified disparities in behavioral health.[18]

Early psychosis and mood disorder detection and intervention and mood disorder programming that occurs across the lifespan.

Outreach and engagement strategies that target early childhood zero to five, out-of-school youth, and secondary school youth. Partnerships with community-based organizations and college mental health and substance use disorder programs may be used to implement the strategies.

Culturally responsive and linguistically appropriate interventions.

Strategies targeting the mental health and substance use disorder needs of older adults.

Strategies targeting the mental health needs of eligible children and youth, as defined in W&I Code section 5892, who are zero to five years of age, including, but not limited to, infant and early childhood mental health consultation.

Strategies to advance equity and reduce disparities.

Strategies to address the needs of individuals at high risk of crisis.

Programs that include community-defined evidence practices and evidence-based practices and mental health and substance use disorder treatment services similar to those provided under other programs that are effective in preventing mental illness and substance use disorders from becoming severe and components similar to programs that have been successful in reducing the duration of untreated severe mental illness and substance use disorders to assist people in quickly regaining productive lives.

While the above priorities are required, counties may include other priorities for the use of their BHSS Early Intervention funds based on needs identified in their community planning process, in addition to the established priorities and consistent with Chapter 3, Section B.[19] If a county chooses to include other programs, the Integrated Plan shall include a description of why those programs are included and metrics by which effectiveness of those programs is to be measured.[20] Counties may act jointly to meet these requirements.[21]

A.7.2.1 Childhood Trauma Early Intervention Programs[22]

The BHSA strengthens prioritization of resources to serve eligible children and youth with its dedicated allocation of BHSS Early Intervention funds. County Early Intervention programs must include specific interventions focused on childhood trauma.

These programs target BHSA eligible children and youth exposed to, or who are at risk of exposure to, adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and traumatic childhood events, environmental trauma including community violence, generational trauma, institutional trauma, and prolonged toxic stress. Childhood trauma Early Intervention programs aim to address the early origins of mental health and substance use disorder needs and prevent long-term mental health and substance use disorder concerns. These programs may include, but are not limited to, the following:

Focused outreach and early intervention to at-risk and in-need populations, including youth experiencing homelessness, justice-involved youth, LGBTQ+ youth, and child welfare-involved youth.

Implementation of appropriate trauma and developmental screening and assessment tools with linkages to early intervention services to eligible children and youth who qualify for these services.

Collaborative, strengths-based approaches that appreciate the resilience of trauma survivors and support their parents and caregivers when appropriate.

Support from peer support specialists, wellness coaches, and community health workers trained to provide mental health and substance use disorder treatment services with an emphasis on culturally and linguistically tailored approaches.

Multigenerational family engagement, education, and support for navigation and service referrals across systems that aid the healthy development of children and youth and their families.

Collaboration with county child welfare agencies and other system partners, including Medi-Cal Managed Care Plans, and homeless youth service providers, to address the physical and behavioral health-related needs and social needs of child-welfare-involved youth.

Linkages to primary care and behavioral health settings, including, but not limited to, federally qualified health centers, rural health centers, community-based providers, school-based health centers, school-linked providers, and school- based programs and community-based organizations, early learning and care centers, Regional Centers, school-based health centers, specializing in serving underserved communities.

Linkages to county and community-based organizations that will help address the adolescent’s needs through the provision of continuing care and support services.

Leveraging the healing value of traditional cultural connections and faith-based organizations, including policies, protocols, and processes that are responsive to the racial, ethnic, and cultural needs of individuals served and recognition of historical trauma.

Blended funding streams to provide individuals and families experiencing toxic stress comprehensive and integrated supports across systems.

Partnerships with local educational agencies and school-based behavioral health professionals, early learning and care centers, county First Five commissions, and Regional Centers, to identify and address children exposed to, or who are at risk of exposure to, adverse and traumatic childhood events and prolonged toxic stress.

A.7.3 Early Intervention Program Components

Each county must establish and administer an Early Intervention program that is designed to prevent mental illnesses and substance use disorders from becoming severe and disabling and to reduce disparities in behavioral health. County Early Intervention programs must include the following components[23]:

Outreach

Access and linkage to care

Mental health and substance use disorder early treatment services and supports

All services and supports provided within county Early Intervention programs must meet the requirements of their respective component.

A.7.3.1 Outreach

Outreach is the process of engaging, encouraging, educating, training, and learning about ways to recognize and respond effectively to early signs of potentially severe and disabling mental health and substance use disorders.[24] Outreach activities funded under BHSS Early Intervention must meet the following requirements:

Be directed towards eligible high-risk individuals within BHSA priority populations,[25] including older adults[26] and youth.[27]

Have the goal of identifying individuals for access and linkage to services and supports.

Connect eligible individuals directly to access and linkage programs or to mental health and substance use disorder treatment services and supports, should an individual wish to be connected to services.

County outreach activities may include those that target:

Families

Employers

Primary care health care providers

Behavioral health urgent care and first responders

Hospitals, inclusive of emergency departments

Education, including early care and learning, TK-12, higher education

Community-based organizations that specialize in serving underserved communities

Others

Eligible older adults and youth may require tailored outreach strategies, as noted below.

Outreach Strategies for Older Adults

When targeting the mental health and substance use disorder needs of BHSA eligible older adults, outreach strategies include, but are not limited to, the following[28]:

Outreach and engagement strategies that target caregivers, victims of elder abuse, and individuals who live alone.

Outreach to older adults who are isolated and/or lonely.

Programs for early identification of mental health disorders and substance use disorders.

Outreach to organizations that provide services to older adults such as Area Agencies on Aging, Caregiver Resource Centers, and Aging and Disability Resource Connections.

Youth Outreach and Engagement

Youth outreach and engagement strategies target BHSA eligible out-of-school youth and secondary school-age youth, and include, but are not limited to, the following[29]:

Establishing direct linkages for youth to community-based mental health and substance use disorder treatment services.

Participating in EBPs and CDEP programs for mental health and substance use disorder treatment services.

Providing supports to facilitate access to services and programs, including those utilizing EBPs and CDEPs, for underserved and vulnerable populations, including, but not limited to, members of ethnically and racially diverse communities, members of the LGBTQ+ communities, victims of domestic violence and sexual abuse, and veterans.

Establishing direct linkages for students to community-based behavioral health services for which reimbursement is available through the students’ health coverage.

Reducing racial disparities in access to behavioral health services.

Providing school employees and students with education and training in early identification, intervention, and referral of students with behavioral health needs.

Providing education and training opportunities in early identification, intervention, and referral of youth with behavioral health needs in community- based settings to target out-of-school youth and employees of organizations that work with youth.

Providing strategies and programs for youth with signs of behavioral or emotional needs or substance misuse who have had, or are at risk of having, contact with the child welfare or juvenile justice system.

Providing integrated youth behavioral health programming.

A.7.3.2 Access and Linkage to Care

Access and linkage to care must ensure that care can be provided by county behavioral health programs as early in the onset of behavioral health conditions as practicable, and that referrals for medical and social services are provided as needed.[30] Access and linkage to care may include activities that support screening, assessment, and referral to behavioral health services, such as telephone help lines, mobile response teams, and supportive services such as Enhanced Care Management and Community Supports available to Medi-Cal members. Activities must also include the scaling of and referral to the Early Psychosis Intervention (EPI) Plus Program, including Coordinated Specialty Care, or other EBPs and CDEPs for early psychosis and mood disorder detection and intervention programs.[31]

A.7.3.3 Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Services and Supports

Mental health and substance use disorder treatment services and supports provided under Early Intervention must be proven to reduce the duration of untreated serious mental health illnesses and substance use disorders and assist people in quickly regaining productive lives.[32],[33] Early intervention mental health and substance use disorder services must also be responsive to the cultural and linguistic needs of diverse communities.[34]

When determining what practices to implement locally, counties may reference the biennial DHCS-provided list of EBPs and CDEPs.[35] More information on EBPs and CDEPs can be found in Chapter 7, Section A.7.6.

Early intervention mental health and substance use disorder treatment services and supports to those eligible for BHSA may include:

Mental health treatment services to address first episode psychosis.

Mental health and substance use disorder services that prevent, respond, or treat a behavioral health crisis or activities that decrease the impacts of suicide, return to use of illicit substances or misuse of prescription drugs, and/or accidental overdose/poisoning.

Early intervention services designed to address co-occurring mental health and substance use issues.

In addition to the BHSA Eligible Populations, early intervention mental health and substance use disorder services may be provided to the following eligible children and youth.

Individual children and youth at high risk for a behavioral health disorder due to experiencing trauma, as evidenced by scoring in the high-risk range under a trauma screening tool such as an ACEs screening tool,[36] involvement in the child welfare system or juvenile justice system or experiencing homelessness.

Individual children and youth in populations with identified disparities in behavioral health outcomes.

A.7.4 Stigma and Discrimination Reduction

Stigma and discrimination reduction activities aim to reduce negative feelings, attitudes, beliefs, perceptions, stereotypes, and/or discrimination related to being diagnosed with a mental illness, substance use disorder or seeking behavioral health services. Stigma and discrimination reduction programs align with population-based prevention activities and cannot be funded with Early Intervention funding.

A.7.5 Early Psychosis Intervention Plus Programs[37]

Early Psychosis Intervention (EPI) Plus programs encompass early psychosis and mood disorder detection and intervention. These programs utilize evidence-based approaches and services to identify and support clinical and functional recovery of individuals by reducing the severity of first, or early, episode psychotic symptoms and other early markers of serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia spectrum disorders and mood disorders, supporting individuals to engage in school or at work, and putting them on a path to better health and wellness.[38] EPI Plus programs may include, but are not limited to, all of the following:

Focused outreach to at-risk and in-need populations, as applicable.

Recovery-oriented psychotherapy, including cognitive behavioral therapy focusing on co-occurring disorders.

Family psychoeducation and support.

Peer support services.

Supported education and employment.

Pharmacotherapy and primary care coordination.

Use of innovative technology for mental health information feedback access that can provide a valued and unique opportunity to assist individuals with mental health needs and to optimize care.

Case management.

EPI Plus programs must include CSC for FEP and may include other EBPs and CDEPs for early psychosis and mood disorder detection and intervention programs. See CSC for FEP requirements below.

A.7.5.1 Coordinated Specialty Care for First Episode Psychosis

CSC for FEP is a community-based service that provides timely and integrated support during the critical initial stages of psychosis with the strongest base of evidence among any intervention for improving outcomes for individuals experiencing early psychosis. CSC for FEP reduces the likelihood of psychiatric hospitalization, emergency room visits, residential treatment placements, involvement with the criminal justice system, substance use, and homelessness that are often associated with untreated psychosis.[39],[40] Research on CSC for FEP has demonstrated that individuals who receive this service are significantly less likely to develop a significant mental health condition over time compared to those who receive standard care.[41] Individuals who receive CSC for FEP have also reported improved psychopathology and overall quality of life.[42] DHCS and the Mental Health Services Oversight and Accountability Commission (MHSOAC) have made significant investments in expanding CSC for FEP throughout the state, such as through funding, technical assistance, and policy reforms. These efforts include contracting with University of California, Davis to fund FEP technical assistance for county behavioral health agencies, a $25 million commitment to further support and expand EPI-CAL, Assembly Bill (AB) 1315 establishment of the EPI Plus program, Children and Youth Behavioral Health Initiative (CYBHI) grants for CSC for FEP, and coverage of CSC for FEP as a bundled service under Behavioral Health Community-Based Organized Networks of Equitable Care and Treatment (BH-CONNECT).

County Early Intervention programs must implement CSC for FEP beginning July 2026. In addition to utilizing EI funds under BHSS, counties may meet the requirement to implement CSC for FEP programs using other non-BHSA funding sources including, but not limited to 2011 Realignment or Mental Health Block Grant funding, so long as this is accounted for in their Integrated Plan. To support implementation, DHCS will make available training, technical assistance, and fidelity monitoring supports for counties as they implement CSC for FEP.

Between July 1, 2026, and June 30, 2029, all counties[43] must:

Participate in ongoing training and technical assistance.

Understand gaps to fidelity by December 31, 2027.

Complete full fidelity reviews and demonstrate counties are implementing CSC for FEP with fidelity by June 30, 2029.

A.7.5.2 Aligning Coordinated Specialty Care for First Episode Psychosis in Early Intervention with Medi-Cal

In December 2024, CMS approved State Plan Amendment (SPA) 24-0042, which establishes CSC for FEP as a covered benefit in the Medi-Cal program. Counties have the option to provide CSC for FEP as a bundled service with a monthly bundled reimbursement rate under Medi-Cal in the Specialty Mental Health Services (SMHS) delivery system beginning in 2025.[44]

Counties should use the BH-CONNECT EBP Policy Guide to support implementation of CSC for FEP. The EBP Policy guide includes information about the evidence-based service criteria for CSC for FEP, staffing structure for teams of behavioral health practitioners delivering CSC for FEP, and other best practices for delivering CSC for FEP with fidelity to the evidence-based model.

In addition, all counties must adhere to the training, technical assistance and fidelity requirements identified in the forthcoming BH-CONNECT EBP Behavioral Health Information Notice (BHIN). The BH-CONNECT EBP BHIN also includes coverage, payment and other compliance requirements for counties that elect to cover CSC for FEP in Medi-Cal.

Counties that do not choose to offer CSC for FEP as a bundled Medi-Cal service are still required to deliver and bill Medi-Cal for medically necessary unbundled CSC for FEP services covered as SMHS.

These services may include the following SMHS:

Assessment

Crisis Intervention

Medication Support Services

Peer Support Services

Psychosocial Rehabilitation

Referral and Linkages

Therapy

Treatment Planning

Even if counties do not opt to take up the option to provide CSC for FEP as a bundled Medi-Cal service, counties must deliver CSC for FEP with fidelity and consistent with the requirements established for BH-CONNECT. For non-Medi-Cal BHSA eligible individuals, Early Intervention funding may be used for the fully uninsured. Commercial health plans are required to provide coverage for CSC for FEP under Senate Bill (SB) 855 regulations[45] and counties are required to seek reimbursement from commercial payers; see section C.3.3 regarding how to file a complaint with the appropriate regulatory agency.[46]

A.7.6 Biennial List of Evidence-based Practices and Community- Defined Best Practices

DHCS will develop a non-exhaustive list of Early EBPs and CDEPs biennially.[47] The biennial list is an optional reference tool to support each county behavioral health department’s community planning process discussions regarding which practices to implement locally.

The only EBP that counties are required to provide as a part of Early Intervention is a CSC for FEP program, beginning July 2026. However, DHCS may require a county to implement a particular EBP or CDEP from the DHCS biennial list.[48]

Counties can include other county-specific CDEPs and can innovate and implement emerging and promising practices that are not included on the biennial list of EBPs and CDEPs provided by DHCS in their IP.

An Early Intervention EBP or CDEP on the biennial list may include population-based prevention elements. Counties will still be able to fund EBPs and CDEPs that may have very limited population-based prevention components in full with BHSS funds only if the EBP or CDEP is on the biennial list developed by DHCS.

DHCS leverages the following sources to identify EBPs and CDEPs:

BH-CONNECT[49]

Children and Youth Behavioral Health Initiative’s (CYBHI) EBPs and CDEPs grant program[50]

Family First Prevention Services Act[51]

Blueprints for Healthy Youth Programs[52]

The Athena Forum created by Washington State Health Care Authority[53]

CDPH’s California Reducing Disparities Project[54]

Evidence-based Practices Resource Center developed by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration[55]

The Cognitive-Behavioral Interventions for Substance Use curriculum designed by the University of Cincinnati[56]

California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare[57]

The County of Los Angeles Department of Mental Health, Prevention and Early Intervention EBPs, Promising Practices, and CDEPs Resource Guide 2.0. created by the California Institute for Mental Health[58]

B. Full Service Partnership

B.1 Full Service Partnership Funding

Counties are required to use 35 percent of the funds distributed by the State Controller’s Office into their Behavioral Health Services Fund (BHSF) for Full Service Partnership (FSP).

B.2 Introduction and Background

FSP programs provide individualized, team-based care to individuals living with significant behavioral health needs through a “whatever it takes” approach. Participants benefit from a community-based, whole-person approach that is trauma-informed, recovery-focused, age-appropriate, and delivered in partnership with families or an individual’s natural supports.

County FSP programs have been a core Mental Health Services Act (MHSA) investment over the last 20 years and continue to be a key component of California’s behavioral health continuum of care. FSP programs were developed from the early successes of late-90s’ pilot programs “to fund comprehensive and integrated care for persons with high risk for homelessness, justice involvement, and hospitalization.”[59] While evaluations have found that county FSP programs achieve improved outcomes for FSP participants and cost savings, there is variance in county models and limited information available on the effectiveness of county FSP programs and the overall FSP initiative.[60] A 2024 Mental Health Services Oversight and Accountability Commission (MHSOAC) publication identified opportunities to improve FSP programs, many of which are reflected in the Behavioral Health Services Act (BHSA). The recommendations include[61]:

Establish a common set of service requirements.

Develop standardized definitions and eligibility requirements.

Develop a tiered system for FSP care and incorporate step-down planning into programs.

Ensure FSP programs are equipped to serve a diverse population.

Streamline data collection and clarify expectations.

Many policy changes that will be implemented under the BHSA are responsive to these MHSOAC recommendations. Under BHSA, FSP policies will include standardization of key evidence-based practices (EBPs) that must be included as part of county FSP programs across service delivery systems, a tiered model with opportunity for step-down planning, and greater consistency in FSP programs from county to county.

B.3 Full Service Partnership Program Requirements

B.3.1 Eligible and Priority Populations

FSP Eligible Populations include:

Behavioral Health Services Act (BHSA) eligible adults and older adults, who meet the priority population criteria specified in W&I Code section 5892, subdivision (d), and

BHSA eligible children and youth, which includes transitional age youth (TAY).

B.3.2 Baseline Requirements

Given the expansion to include eligible individuals living with substance use disorder (SUD) in the BHSA, county FSP programs must include SUD treatment services where appropriate. County FSP teams must be capable of supporting FSP participants living with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorder conditions by providing integrated behavioral health care as part of the FSP program, inclusive of mental health, SUD and/or co-occurring services, or by closely coordinating the provision of SUD care for FSP participants.

FSP services shall be provided in accordance with demonstrated clinical need and in alignment with the required high intensity service models: Assertive Community Treatment (ACT), Forensic ACT (FACT), FSP Intensive Case Management (ICM), and High Fidelity Wraparound (HFW).[62] Please refer to the respective sections for details regarding required services and expectations for co-occurring capabilities.

County FSP programs must provide ongoing engagement services to FSP participants in order to maintain their continued treatment.[63] These services may include clinical and recovery-oriented services, such as consumer-operated services, peer support services, transportation, and services to support maintaining housing.[64]

County FSP programs must also include outpatient behavioral health services, either clinic or field based, necessary for the ongoing evaluation, and stabilization and recovery of an enrolled individual. Many of these outpatient behavioral health services are incorporated within the high intensity service models (ACT, FACT, FSP ICM, and HFW) county FSP programs are required to utilize.

FSP teams are required to coordinate with an FSP program participant’s primary care provider as appropriate. Ensuring coordination across systems, including primary care, is critical to participant engagement and satisfaction.[65]

B.3.3 Full Service Partnership Continuum

In accordance with W&I Code section 5887, county FSP programs must make the following specified services available:[66]

Mental health services, supportive services, and substance use disorder (SUD) services

Assertive Community Treatment (ACT)

Forensic ACT (FACT)

FSP Intensive Case Management (ICM)[67]

Individual Placement and Support (IPS) model of Supported Employment

High Fidelity Wraparound (HFW)

Assertive field-based initiation for SUD

Outpatient behavioral health services for evaluation and stabilization

Ongoing engagement services

Service Planning[68]

Housing Interventions (funded under the Housing Interventions category)

County FSP programs may additionally include behavioral health services the county determines are beneficial to an eligible individual's treatment, if not already covered by ACT, FACT, FSP ICM, or HFW, in collaboration with the individual and, when appropriate, the individual's family. Additional services that may be offered in addition to or in conjunction with the specified services listed above include but are not limited to:

Primary SUD FSPs

Additional evidence-based practices (EBPs)

Outreach

Other recovery-oriented services, including consumer-operated services and peer support services

Counties may use FSP funding for outreach activities if the activities relate to enrolling individuals living with significant behavioral health needs in an FSP.[69] For example, counties are encouraged to use data systems (e.g., Medi-Cal Connect) to identify individuals who are not actively receiving behavioral health care through the county yet meet clinical criteria for FSP, and conduct targeted outreach to those individuals. For individuals receiving one of the required EBPs, initial outreach and ongoing engagement is embedded in the model. General outreach to individuals living with significant behavioral health needs who are not FSP eligible should be funded under other appropriate funding sources including Behavioral Health Services and Supports (BHSS) and Housing Interventions.

B.3.4 Full Service Partnership Exemptions

Fiscal Year (FY) 2026-2029 Integrated Plan

State law permits counties with a population of less than 200,000 to request an exemption from the FSP requirements in W&I Code section 5887, subdivision (a)(2). For the first Integrated Plan covering fiscal years 2026-2029, all counties, regardless of their size, will be exempt from the EBP fidelity requirements for ACT, FACT, IPS Model of Supported Employment, and HFW. Therefore, counties do not need to request an exemption from FSP EBP requirements in their first Integrated Plan. DHCS will make available training, technical assistance, and fidelity monitoring supports for counties as they implement FSP EBPs: ACT, FACT, IPS and HFW. Counties are still required to begin offering the required EBPs by July 1, 2026.

To meet FSP EBP requirements, between July 1, 2026, and June 30, 2029, all counties must:

Participate in ongoing training and technical assistance for all FSP EBPs.

Understand gaps to fidelity for each FSP EBP by December 31, 2027.

Complete full fidelity reviews and demonstrate counties are implementing all FSP EBPs with fidelity by June 30, 2029.[70]

FY 2029-2032 Integrated Plan

Subject to DHCS approval, for the second Integrated Plan covering fiscal years 2029- 2032, small counties (population less than 200,000) may request an exemption from the ACT and FACT EBP. Small counties may also request an exemption from IPS and HFW[71] EBP fidelity requirements.

The criteria for FSP exemption requests include:

Limited workforce (e.g., providers)

Limited need (e.g., the number of individuals eligible is too small for the county to support the required EBP staffing for fidelity)

Other considerations, subject to evidence requirements and DHCS review

Counties may use the findings from COE fidelity reviews and other data to determine whether they will seek an exemption in fiscal year 2029. Exemption requests must include:

Documentation demonstrating that one or more of the criteria for exemption are met (e.g., workforce or county demographic data, COE informational fidelity review findings).

A description of how counties will work towards improving fidelity scores or for counties that may never meet fidelity requirements, an explanation of why.

B.3.5 Full Service Partnership Co-Occurring Capabilities

The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) Criteria, Fourth Edition defines co- occurring capable as “Achieving co-occurring capability involves looking at all aspects of program design and functioning to embed integrated policies, procedures, practices, and training in the operations of the program to make it routine for clinicians to successfully delivery integrated care.” FSP participants deserve access to co-occurring care consistent with industry standards. To that end, county FSP programs are required to implement the following:[72]

Connecting individuals to FSP teams, SUD providers, or other clinically necessary services including peer support, as appropriate, after they receive assertive field-based initiation for substance use disorder (SUD) treatment services.

Conducting ASAM screening as part of an integrated assessment upon intake into the FSP, and connecting individuals to SUD providers, as appropriate.

Offering medications for addiction treatment (MAT) services directly to clients or having an effective referral process in place (i.e., established relationship with a MAT provider and transportation to appointments for MAT).[73]

Equipping FSP program staff at all levels of care to provide comprehensive care to individuals living with significant co-occurring behavioral health needs (e.g., motivational interviewing, engagement, and training for prescribers who are not familiar or comfortable with prescribing MAT).

Developing strategies for billing and claiming the appropriate service/delivery system within the context of co-occurring care delivery (e.g., Medi-Cal Specialty Mental Health Services (SMHS) versus Drug Medi-Cal (DMC)/Drug-Medi-Cal Organized Delivery System (DMC-ODS).

For individuals living with SUD only, DHCS will allow but will not require SUD-only FSPs (see additional information in the Substance Use Disorder Primary Full Service Partnership Option section).

B.4 Full Service Partnership Levels of Care

Pursuant to W&I Code section 5887, subdivision (e), county Full Service Partnership (FSP) programs are required to have a standard of care, with levels of care to treat individuals based on acuity. The following subsections outline the requirements for the levels of care as they pertain to adults and to children and youth.

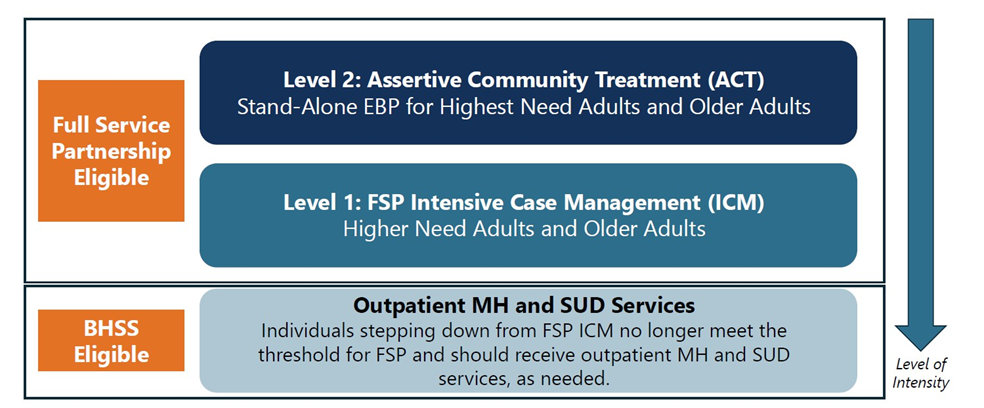

Behavioral Health Services Act (BHSA) Eligible Adults and Older Adults:

For BHSA eligible adults and older adults, two levels of coordinated care must be available depending on individualized need for service intensity. These are ACT, a stand-alone EBP as the highest intensity level, and FSP Intensive Case Management (ICM), which can be a standardized step-down level from ACT, or provided in order to avert the higher ACT level of care (see Figure 7.B.4.1). FSP ICM is for individuals who may not meet ACT eligibility criteria, but still have significant behavioral health needs and can benefit from FSP supports. Individuals stepping down from FSP ICM who no longer meet the threshold for FSP level of need can receive outpatient mental health (MH) and SUD services, funded through Behavioral Health Services and Supports (BHSS).

As described in subsequent sections of this manual, county BHSA FSP programs must implement EBPs in alignment with Medi-Cal guidance (where applicable). Medi-Cal guidance may include eligibility criteria and/or guidelines on clinical indicators of need for an ACT level of care. However, DHCS recognizes the role of the clinician and her/his team in determining an individual’s appropriate level of care, and that movement between tiers may not be linear (i.e., the FSP participant may also need to step back up a level). DHCS will not establish requirements for standardized assessments specific to determining FSP levels of care; this is left to counties and to the clinical judgment and discretion of the treating provider. Under BH-CONNECT, DHCS anticipates issuing guidance for use of one or more Level of Care tools (guidance forthcoming). This guidance may assist counties with identifying individuals who need an FSP level of care but commonly used Level of Care tools do not differentiate between levels of high-intensity, community-based care, such as between ACT and FSP ICM.

Figure 7.B.4.1. FSP Levels of Care

BHSA Eligible Children and Youth:

For BHSA eligible children and youth, counties shall provide High Fidelity Wraparound (HFW), an especially high intensity, comprehensive, holistic, youth and family-driven way of responding when children or youth experience significant behavioral health challenges. HFW is not restricted to children and youth receiving foster care or involved with child welfare and is intended to support a diverse range of needs and systems interaction.

HFW is the designated FSP level of care for children and youth. However, any child or youth may alternatively receive ACT or FSP ICM, if determined to be clinically and developmentally appropriate.

Among children and youth enrolled in HFW, the array of services required may vary based on individual need. In general, there is little evidence that an additional, lower level of case management – i.e., an approach “beneath” HFW – is effective for children and youth with significant behavioral health needs. As such, DHCS is not currently using its authority under W&I Code section 5887, subdivision (e) to require counties to develop multiple, dedicated levels of case management for FSP for children/youth.

BHSA Eligible Transitional Age Youth (TAY):

BHSA eligible TAY (aged 16-25) and those younger than TAY, may receive ACT, FACT, FSP ICM, or HFW if determined to be clinically and developmentally appropriate by the provider and FSP eligible individual. BHSA eligible TAY are included in the definition for “Eligible children and youth.”[74] Counties shall design FSP programming to meet the needs of all BHSA eligible individuals, including TAY.

Counties must make the appropriate EBP for FSP participants available based on clinical judgment and discretion reflecting individualized needs.

B.4.1 Level 2: Assertive Community Treatment and Forensic Assertive Community Treatment

B.4.1.1 Overview

ACT is an evidence-based practice to support individuals living with complex and significant behavioral health needs and a treatment history that may include psychiatric hospitalization and emergency room visits, residential treatment, involvement with the criminal justice system, homelessness, and/or lack of engagement with traditional outpatient services. ACT is one of the most established and widely researched evidence-based practices in behavioral health care for individuals living with significant mental illness.[75],[76],[77] It has been extensively studied across various populations and settings around the world, with evidence supporting its effectiveness across rural areas, urban centers, and among homeless populations.[78],[79]