2. Behavioral Health Transformation

A. Introduction to Behavioral Health Transformation

In recent years, California has undertaken historic efforts to re-envision the state’s publicly funded mental health and substance use disorder (SUD) services, with a special focus on county-administered specialty mental health and substance use disorder services. In March 2024, voters approved Proposition 1 to reform the Mental Health Services Act (MHSA) and fund needed behavioral health facility infrastructure through a general obligation bond. The efforts to implement Proposition 1 are referred to as Behavioral Health Transformation (BHT).

The primary goals of BHT are to improve access to care, increase accountability and transparency for publicly funded, county-administered behavioral health services, and expand the capacity of behavioral health care facilities across California. Under BHT, county reporting will be uniform to allow for comprehensive and transparent reporting of the Behavioral Health Services Act (BHSA) funding in relation to all public local, state, and federal behavioral health funding.

BHT builds upon and aligns with other major behavioral health initiatives in California including the California Advancing and Innovating Medi-Cal (CalAIM) initiative, the California Behavioral Health Community-Based Organization Networks of Equitable Care and Treatment (BH-CONNECT) initiative, the Children and Youth Behavioral Health Initiative (CYBHI), Medi-Cal Mobile Crisis services, the Behavioral Health Bridge Housing program, the Community Assistance, Recovery, and Empowerment (CARE) Act, Lanterman-Petris-Short Conservatorship reforms, 988 expansion, and the Behavioral Health Continuum Infrastructure Program (BHCIP).

California continues to face behavioral health challenges impacted by many factors, including but not limited to the lack of affordable housing and increasing homelessness,[1] the behavioral health workforce shortage,[2] a youth mental health crisis,[3] an older adult mental health crisis,[4] and a shortage of culturally-responsive and diverse care.[5] Many of these challenges make it difficult for individuals to navigate California’s behavioral health care delivery systems and access services at the right time and in the right place. For example, 2022 survey research suggests that 23.5 percent of adult Californians across all payers living with a mental illness reported they did not receive the treatment they needed.[6]

A.1 Bond

In addition to reforming the MHSA, Proposition 1 includes the Behavioral Health Infrastructure Bond Act of 2023. This bond authorizes $6.38 billion to build new behavioral health treatment beds and supportive housing units to help serve more than 100,000 people annually. This investment creates new, dedicated housing for people experiencing or at risk of homelessness who have behavioral health needs, with a dedicated investment to serve veterans. These settings will provide Californians experiencing behavioral health conditions with places to stay while safely stabilizing, healing, and receiving ongoing support.

Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) will administer $4.4 billion of these funds to provide grants to public and private entities for behavioral health treatment and residential settings. $1.5 billion of the funds administered by DHCS will be awarded only to counties, cities, and tribal entities (with $30 million set aside for tribes).

The California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) will administer up to $2 billion to support permanent supportive housing for individuals, including veterans, at risk of or experiencing homelessness and behavioral health challenges.

A.2 Behavioral Health Continuum Infrastructure Program

In 2021, DHCS was authorized to establish the Behavioral Health Continuum Infrastructure Program (BHCIP) and award $2.1 billion in funding to construct, acquire, and expand properties and invest in mobile crisis infrastructure related to behavioral health. DHCS has been releasing these funds through multiple grant rounds targeting various gaps in the state’s behavioral health facility infrastructure.

The Behavioral Health Bond Act of 2023 leverages the success of BHCIP and authorizes DHCS to award up to $4.4 billion for BHCIP competitive grants.[7] Please refer to the BHCIP webpage for the latest information.

B. Overview of the Behavioral Health Services Act

B.1 Behavioral Health Services Act Goals

The Behavioral Health Services Act (BHSA) is the first major structural reform of the Mental Health Services Act (MHSA) since it was passed in 2004. The MHSA imposed a 1 percent tax on personal income over $1 million. Counties and two city-operated mental health authorities receive these funds monthly to provide community-based mental health services. The MHSA was designed to serve individuals with serious mental illness (SMI) and individuals that may be at risk of developing serious mental health conditions.[8] The MHSA created a broad continuum of prevention, early intervention, innovative programs, services, and infrastructure, technology, and training elements. MHSA has been a crucial resource to increase access to mental health services for all eligible populations.

The reforms within the BHSA expand the types of behavioral health supports available to Californians who are eligible for services and are in need by focusing on historical gaps and emerging policy priorities. The key opportunities for transformational change within the BHSA include:

Reaching and Serving High Need Priority Populations

Restructures funding allocations for the BHSA program components by focusing allocations on the areas of most significant need among Californians, including individuals across the lifespan at risk of or experiencing justice and system involvement, homelessness, and institutionalization.

Prioritizes early intervention, especially for children and families, youth, and young adults, to provide early linkage to services and prevent mental health conditions, co-occurring disorders, and substance use disorders from becoming severe and/or disabling.

Prioritizes serving individuals experiencing homelessness or at risk of homelessness, especially individuals and families experiencing long-term homelessness. The BHSA dedicates revenue for counties to assist those with severe behavioral health needs to be housed and provides a path to long-term recovery, including one-time and allowable ongoing capital to build more housing options.

Updates Full Service Partnerships (FSP) requirements to better serve individuals with the most significant needs by requiring FSP programs to include specified, evidence-based delivery models, community-defined evidence practices, and standardized levels of care.

Aligns with initiatives aimed at improving care for Medi-Cal members living with significant behavioral health needs such as the California Advancing and Innovating Medi-Cal (CalAIM) initiative, the California Behavioral Health Community-Based Organization Networks of Equitable Care and Treatment (BH-CONNECT) initiative, the Children and Youth Behavioral Health Initiative (CYBHI), Medi-Cal Mobile Crisis Services, the Behavioral Health Bridge Housing program, the Community Assistance, Recovery, and Empowerment (CARE) Act, Lanterman-Petris-Short Conservatorship reforms, 988 expansion, and the Behavioral Health Continuum Infrastructure Program (BHCIP).

Increasing Access to Substance Use Disorder Services, Housing Interventions, and Evidence-Based and Community-Defined Practices, and Building the Behavioral Health Workforce

Expands the categories of services that may be funded with BHSA dollars to include treatment for substance use disorders, regardless of the presence of a co-occurring mental health condition.

Provides ongoing funding for counties to assist people living with significant mental health conditions, substance use disorder needs and co-occurring behavioral health needs with housing and provides a path to long-term recovery, including one-time and allowable ongoing capital to build more housing options.

Increases investments in the behavioral health workforce including efforts to support more culturally, linguistically, and age-appropriate care by building a more representative workforce.

Requires implementation of specified evidence-based and community-defined evidence practices to improve outcomes for youth and adults with complex behavioral health conditions.

Focusing on Outcomes, Transparency, Accountability, and Equity

Requires counties to complete a county Integrated Plan for behavioral health services and outcomes, which will include information on all local behavioral health funding and services, including Medi-Cal and non-Medi-Cal specialty behavioral health programs and funding streams.

Requires counties to complete an annual county Behavioral Health Outcomes, Accountability, and Transparency Report (BHOATR) to provide public visibility into county spending, disparities, and results.

Utilizes data through the lens of health equity to identify racial, ethnic, age, gender, and other demographic disparities and inform disparity reduction efforts.

County BHSA programs must include culturally responsive and linguistically appropriate interventions. These interventions must be able to reach underserved cultural populations and address specific barriers related to racial, ethnic, cultural, language, gender, age, economic, or other disparities in mental health and substance use disorder treatment services access, quality, and outcomes.

B. Overview of the Behavioral Health Services Act

B.2 Timeline for Implementation

Table B.2.1. Timeline for Implementation

Requirement | Effective Date |

Counties Submit Draft FY 2026-2029 County Integrated Plan to DHCS with County Administrative Officer (CAO) Approval | No later than March 31, 2026 |

Counties Submit Final FY 2026-2029 County Integrated Plan to DHCS County Board of Supervisors Approve Final Fiscal Year (FY) 2026-2029 County Integrated Plan | No later than June 30, 2026 |

County Integrated Plans Are Effective | July 1, 2026 |

Counties Submit Draft 2027-2028 County Annual Update to DHCS with CAO Approval | No later than March 31, 2027 |

Counties Submit Final FY 2027-2028 County Annual Update to DHCS County Board of Supervisors Approve Final FY 2027-2028 County Annual Update | No later than June 30, 2027 |

Submit Draft FY 2026-2027 County Behavioral Health Outcomes, Accountability, and Transparency Report (BHOATR) | January 30, 2028 |

Submit Final FY 2026-2027 County Behavioral Health Outcomes, Accountability, and Transparency Report (BHOATR) | January 30, 2029 |

B.3 Eligible Populations

Eligible populations are those that may receive services funded by the Behavioral Health Services Act (BHSA) and include children and youth, adults, and older adults who meet BHSA eligibility criteria.

Eligibility criteria for BHSA services are aligned with Medi-Cal specialty mental health services (SMHS) access criteria,[9] and include individuals with substance use disorders as described below. However, it is important to note that BHSA eligible populations are not required to be enrolled in the Medi-Cal program.[10]

Eligible children and youth means persons who are 25 years of age or under who meet either of the following:

Meet SMHS access criteria specified in subdivision (d) of W&I Code section 14184.402 and implemented in SMHS guidance[11] (includes individuals 21-25 years of age who meet this criteria) OR

Have at least one diagnosis of a moderate or severe substance use disorder from the most current version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) for Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders, with the exception of tobacco-related disorders and non-substance-related disorders.[12]

Eligible adults and older adults means persons who are 26 years of age or older who meet either of the following:

Meet SMHS access criteria specified in W&I Code section 14184.402, subdivision (c) and implemented in DHCS guidance[13] (only applies to individuals 26 years of age and older) OR

Have at least one diagnosis of a moderate or severe substance use disorder from the most current version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) for Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders, with the exception of tobacco-related disorders and non-substance-related disorders.[14]

Priority Populations

In addition to defining the populations eligible for services, the BHSA also requires counties to prioritize BHSA services for the populations listed below.[15] While counties must prioritize BHSA services for the priority populations listed below, access to BHSA services is not limited to these priority populations. At-risk populations should be identified by counties based on local need and local planning processes, except for the criteria for at-risk of homelessness which can be found in the Housing Interventions chapter and below.

Eligible children and youth who satisfy one of the following:

Are chronically homeless or experiencing homelessness or at risk of homelessness[16]

Are in, or at risk of being in, the juvenile justice system[17]

Are reentering the community from a youth correctional facility

Are in the child welfare system pursuant to W&I Code sections 300, 601, or 602

Are at risk of institutionalization[18]

Eligible adults and older adults who satisfy one of the following:

Are chronically homeless or experiencing homelessness or at risk of homelessness[19]

Are in, or at risk of being in, the justice system

Are reentering the community from state prison or county jail

Are at risk of conservatorship[20]

Are at risk of institutionalization[21]

For additional information about criteria or priority populations for Full Service Partnerships and Housing Interventions, including the definition for “chronically homeless”, please refer to the corresponding sections within this manual.

C. Statewide Vision for Behavioral Health Quality and Equity

The state is committed to boldly taking action to provide Californians with quality, culturally responsive behavioral health services when, how, and where they need them.[22] It will take cross-system collaboration and partnership across service delivery systems to address the statewide behavioral health goals discussed in this Policy Manual. DHCS, county behavioral health, Medi-Cal Managed Care Plans (MCPs), commercial plans, commercial plan regulators, and other key delivery system partners such as child welfare, public health, schools and others will share responsibility for improving the well-being of Californians in need of behavioral health services.

C.1 A Population Health Approach to Behavioral Health

The Behavioral Health Transformation presents a historic opportunity to transform behavioral health service delivery by:

Taking a population health approach to align expectations across California’s behavioral health delivery system.

Establishing a vision for quality and equity and setting statewide goals to drive progress across the behavioral health delivery system.

Using data to support continuous quality improvement.

A population health[23] approach aims to address these gaps in access to care and connect individuals to the right services, in the right place, and at the right time.

A population health approach for the behavioral health delivery system[24]:

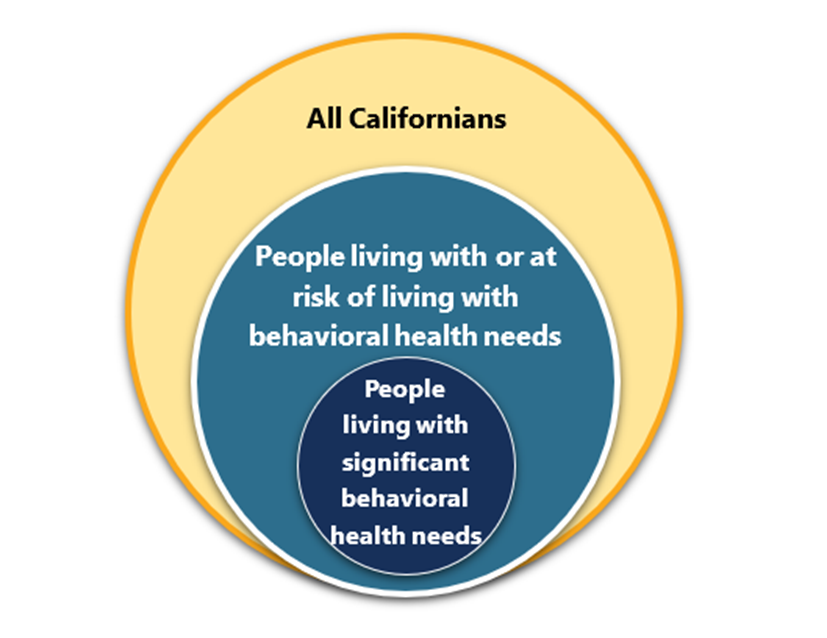

Considers the entire population eligible for public behavioral health services, not just those currently receiving behavioral health services and those seeking care (shown in Figure 2.C.3).

Deploys whole-person care[25] interventions, including addressing social drivers of health, which are the environments in which people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health functioning and quality of life outcomes and risk factors.[26]

Coordinates across service delivery systems, including cross-system collaboration and partnership across county behavioral health, Medi-Cal MCPs, commercial plans, commercial regulators, public health, and other key service delivery partners.

Uses data to:

Identify underserved and unserved population groups for targeted interventions.

Improve quality[27] across the behavioral health care continuum.

Monitor effectiveness of interventions across populations.

Support continuous improvement.

Identify and track racial and ethnic disparities[28] in behavioral health outcomes.

Figure 2.C.3. Population Health Approach to Behavioral Health Quality and Equity

Like the Population Health Management (PHM) Program[29] for Medi-Cal MCPs implemented in January 2023, a population health approach to behavioral health will reorganize and strengthen existing contract requirements, particularly requirements related to collaboration across the delivery system,[30] and is targeted to the delivery system that DHCS oversees.

DHCS will work to align priorities and desired outcomes across the behavioral health delivery system, payers (e.g., Medi-Cal MCP Non-Specialty Mental Health Services (NSMHS) and Medi-Cal Specialty Mental Health Services (SMHS)), initiatives and funding sources (e.g., BHSA,[31] BH-CONNECT, and Realignment and Block Grants), while still allowing for initiative-specific goals.

As outlined in W&I Code section 5963.02, subdivision (c)(3)(A), each county shall develop an Integrated Plan (IP) and annual update (AU) aligned with statewide behavioral health goals and their associated measures. DHCS will begin by defining statewide population behavioral health goals to define the improvements that counties and the state should be working towards together across the behavioral health delivery system. Measures associated with these goals will be developed in phases.

Phase 1 will use population-level behavioral health measures, which are defined as measures of community health and wellbeing associated with the statewide behavioral health goals. Phase 1 measures must be used in the county BHSA planning process and should inform resource planning and implementation of targeted interventions to improve outcomes. They are statewide indicators for which counties are not exclusively responsible; it will take cross-service delivery system collaboration and partnership to move the needle on Phase 1 measures. As part of the 2025 PHM strategy (guidance forthcoming), Medi-Cal MCPs will also be working towards the statewide behavioral health goals and measures.

In Phase 2, measures will be used for monitoring and accountability purposes and will focus on performance of county behavioral health and Medi-Cal MCPs, respectively. The BHSA-funded interventions (e.g., Housing Interventions, Behavioral Health Services and Supports, Full Service Partnerships), as well as county behavioral health SMHS and Medi-Cal MCP NSMHS, should impact the goals outlined in C.3. and their associated measures.

In both phases, counties should utilize the Community Planning Process detailed in the Policy Manual to work with key stakeholders to address the statewide population behavioral health goals.

C.2 Statewide Population Behavioral Health Goals

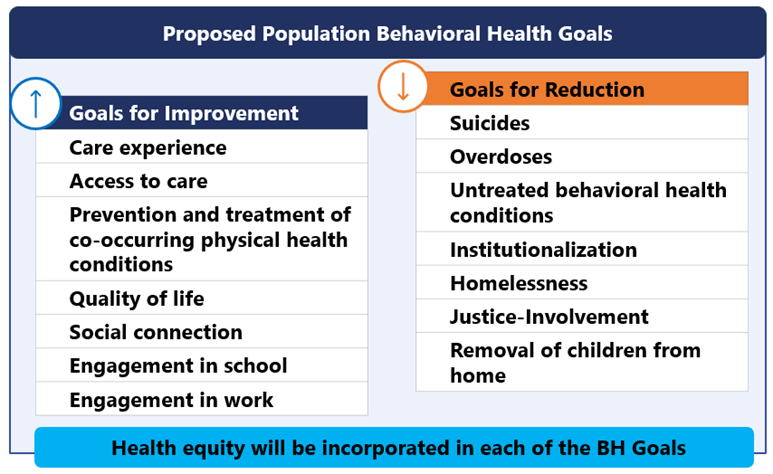

DHCS, in consultation with behavioral health stakeholders and subject matter experts, has identified 14 statewide behavioral health goals[32] focused on improving wellbeing (e.g., quality of life, social connection) and decreasing adverse outcomes (e.g., suicides, overdoses). These behavioral health goals (shown in Figure 2.C.4) will inform state and county planning and prioritization of BHSA resources, and DHCS will continuously assess statewide and county progress toward these goals under BHT.

Note that health equity, defined as the “reduction or elimination of health disparities, health inequities, or other disparities in health that adversely affect vulnerable populations”,[33] will be incorporated in each of the statewide behavioral health goals. DHCS will endeavor to provide measures that can be stratified (e.g., by demographics such as age group and race/ethnicity, etc.) to enable visibility into disparities. In addition to identifying disparities, DHCS will ask counties and Medi-Cal Managed Care Plans (MCPs) to address disparities and DHCS will consider disparities when developing accountability measures.

Figure 2.C.4. Statewide Population Behavioral Health Goals

DHCS selected these goals based on their strong indication of the health and wellbeing of Californians living with significant behavioral health needs. In alignment with the mission of BHT to improve behavioral health for Californians, the statewide population behavioral health goals lay out the vision that the state, counties, MCPs, and other key stakeholders must work towards to improve the overall well-being of Californians who are living with behavioral health needs (see Tables 2.C.1 and 2.C.2 for the goals’ definitions and rationale for inclusion).

Measures associated with each goal are forthcoming.

Table 2.C.1. Statewide Population Behavioral Health Goals: Goals for Improvement – Definition and Rationale

Goals for Improvement | Definition and Rationale |

Care experience | Care experience refers to the range of interactions and quality of care that patients have and receive from the healthcare system that can impact level of engagement and length of treatment.[34] Improving the care experience (e.g., care is culturally congruent and responsive, trauma-informed, etc.) in California’s behavioral health delivery system is important; positive experiences with care can lead to greater treatment engagement, adherence, and remaining in treatment longer, leading to positive health outcomes. |

Access to care | Access to care is defined as the timely and appropriate use of health services to achieve the best possible health outcomes, inclusive of all modalities.[35] Improving Californians’ access to care is necessary for improving outcomes. Compliance with provider availability as outlined in network adequacy requirements, strategies for navigating the complex care delivery system, and improving wait times for appointments will enable Californians to better access the right care at the right time. |

Prevention and treatment of co-occurring physical health conditions | Co-occurrence in this goal refers to the prevention or treatment of a physical health condition in an individual with an existing BH condition. An integrated care approach that addresses both behavioral and physical health needs of individuals can lead to earlier treatment of uncontrolled chronic physical health conditions. |

Quality of life | Quality of life is defined as an individual’s “perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns.”[36] Individuals living with behavioral health conditions face challenges from symptoms and associated stigma, which can negatively impact daily functioning, wellbeing, and overall quality of life. |

Social connection | Social connection refers to the degree to which an individual has the number, quality, and variety of relationships that they want to feel and have belonging, support, and care.[37] Establishing and maintaining supportive relationships is vital for preventing and managing significant behavioral health needs along with other behavioral health conditions associated with loneliness and isolation. |

Engagement in school | In this context, engagement refers to the degree of attention, curiosity, interest, passion, and optimism that an individual has towards school and related activities, including their enrollment and participation in as well as graduation from school.[38] Enhancing engagement through prevention and treatment of behavioral health conditions can enable individuals to participate actively and meaningfully, leading to improvements in quality of life, independence, and wellbeing. |

Engagement in work | Similar to above, engagement refers to the degree of attention, curiosity, interest, passion, and optimism that an individual has towards work and related activities. Enhancing engagement in the workplace as part of paid employment or unpaid work through prevention and treatment of behavioral health conditions can enable individuals to participate actively and meaningfully, leading to improvements in job performance, productivity, job satisfaction, and overall personal wellbeing. |

Table 2.C.2. Statewide Population Behavioral Health Goals: Goals for Reduction – Definition and Rationale

Goals for Reduction | Definition and Rationale |

Suicides | Suicide, including suicide attempts is defined as death or non-fatal, potentially injurious harm caused by self-directed injurious behavior with the intent to die as a result of the behavior.[39],[40] Strengthening California’s behavioral health delivery system and providing targeted and tailored suicide prevention efforts is critical for reducing California’s suicide rate. |

Overdoses | A drug-related overdose can occur when a toxic amount of a drug, or combination of drugs, including prescription, illicit, or alcohol, overwhelms the body.[41] In California, drug-related overdose deaths have doubled since 2017, reaching 10,898 in 2021,[42] with the greatest impact among racial and ethnic minorities, and individuals experiencing homelessness, unemployment, and incarceration. |

Untreated behavioral health conditions | Untreated behavioral health conditions refer to an individual’s behavioral health condition that has not been diagnosed or attended to with appropriate and timely care. Living with untreated behavioral health conditions can lead to worsening symptoms, diminished quality of life, unemployment, reduced educational attainment, homelessness, and higher risk of severe outcomes such as suicide or self-harm. |

Institutionalization | Minimize time in institutional settings by ensuring timely access to community-based services across the care continuum and in a clinically appropriate setting that is least restrictive. Reducing institutionalization entails maximizing community integration and making supportive housing options with intensive, flexible, voluntary supports and services available to all individuals who would benefit. Stays in institutional settings are sometimes clinically appropriate and therefore the goal is not to reduce institutionalization to zero. |

Homelessness | Homelessness is defined below in Section 7.C.4.1.1 of the Housing Interventions chapter. Addressing the increase in statewide homelessness is crucial to ensuring unhoused individuals living with significant behavioral health needs receive regular access to behavioral health treatment and safe and stable housing where they can recover. |

Justice-Involvement | Reducing justice involvement refers to reducing adults and youth living with behavioral health needs who are involved in the justice system - including those who have been arrested, are living in, who are under community supervision, or who have transitioned from a state prison, county jail, youth correctional facility, or other state, local, or federal carcel settings where they have been in custody of law enforcement authorities. More than 50 percent of incarcerated individuals living with a behavioral health condition.[43] While incarcerated, justice-involved individuals living with behavioral health needs have limited access to treatment. Formerly incarcerated individuals are more likely to experience poor health outcomes, including higher risk for injury and death due to violence, overdose, and suicide.[44] Promoting coordinated systems of care between the legal system and behavioral health plans and providers can have an impact on reducing justice involvement and improving outcomes for those who are justice-involved. |

Removal of children from home | Removal of children from home, specifically those with an open child welfare status, refers to when children may be removed from their home due to abuse and/or neglect. Providing early intervention and intensive BH services to parents and additional members of the family unit living with a behavioral health condition can prevent family disruption and improve child welfare outcomes, as children are less likely to be placed in foster care and exposed to early childhood trauma. |

C.3 Population Behavioral Health Framework

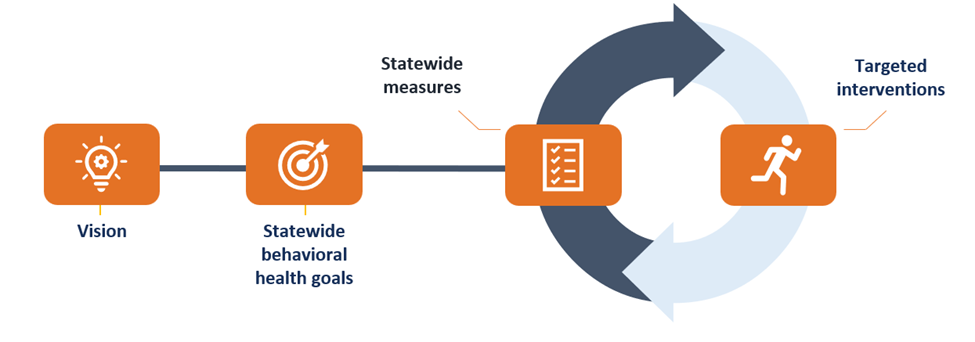

Under BHT, DHCS will partner with counties to participate in a cycle of continuous improvement to drive progress on the statewide behavioral health goals (shown in Figure 2.C.5):

Establish statewide behavioral health goals.

In consultation with behavioral health stakeholders and subject matter experts, identify at least one measure for each behavioral health goal.

Deliver measures to counties describing their performance on the statewide behavioral health goals.

DHCS recognizes that shifting to a coordinated, data-driven, population behavioral health approach will take time. As with the PHM Program, DHCS will phase in requirements and provide technical assistance to counties and other key stakeholders.

Figure 2.C.5. Population Behavioral Health Framework

[1] California Budget and Policy Center. “The Rise of Homelessness Among California's Older Adults.”(May 2024).

[2] Cal Matters. “Mental health workers: Why California faces a shortage.” (September 2022).

[3] Xiang, A., Martinez, M., & Chow, T. “Depression and anxiety among US children and young adults.” Journal of American Medical Association Open.” (2024).

[4] UCLA Health. “California must build workforce to serve older adults’ behavioral health needs, UCLA report says.” (January 2019).

[5] Kaiser Family Foundation.“Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Mental Health Care: Findings from the KFF Survey of Racism, Discrimination and Health.” (May 2024).

[6] Mental Health America. “The State of Mental Health in America.” (2022).

[7] BHCIP Request for Applications

[10] W&I Code § 5892, subdivision (k)

[12] W&I Code § 5891.5, subdivision (c)

[14] W&I Code § 5891.5, subdivision (c)

[15] W&I Code §5892, subdivision (d)

[16] Additional information and definitions should be referenced in the Housing chapter below. Chapter 7.C.

[18] The DHCS ECM Guide defines institutionalization as “broad and means any type of inpatient, Skilled Nursing Facility, long-term, or emergency department setting.”

[19] Additional information and definitions should be referenced in the Housing chapter below. Chapter 7.C.

[21] The DHCS ECM Guide defines institutionalization as “broad and means any type of inpatient, Skilled Nursing Facility, long-term, or emergency department setting.”

[22] California Health and Human Services. “Policy Brief: Understanding California’s Recent Behavioral Health Reform Efforts.” (March 2023).

[23] Population health is defined as the health of all individuals in a defined group, and the interdisciplinary, cross-sector approach that brings health-related resources together with medical care to achieve positive health outcomes for a defined group. This definition is derived from the American Journal of Public Health’s article, “What is Population Health?”.

[24] The population health approach for behavioral health is adapted from the population health strategy for DHCS’ Population Health Management.

[25] Whole-person care is an approach that coordinates physical, behavioral, and social services in a patient-centered manner to address needs comprehensively and improve the overall health and wellbeing of individuals. This definition is derived from DHCS’ Whole Person Care Pilots.

[26] SDOH definition is derived from the DHCS Population Health Management Policy Guide.

[27] The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) defines “quality [in healthcare]” as “providing the right care at the right time in the right way for the right person and having the best results possible”: Best Practices in Public Reporting No. 2: Maximizing Consumer Understanding of Public Comparative Quality Reports: Effective Use of Explanatory Information.

[28] “Disparities” is defined as the preventable differences in the burden of disease, injury, violence, or opportunities to achieve optimal health, health quality, or health outcomes that are experienced by underserved populations. Source: Adapted from CDC.

[29] DHCS’ Population Health Management (PHM) Program is a cornerstone of CalAIM.

[30] See for example the Memorandum of Understanding between [Medi-Cal Managed Care Plan] and [Mental Health Plan] template

[31] The Behavioral Health Services Act replaces the Mental Health Services Act of 2004. It reforms behavioral health care funding to prioritize services for people with the most significant mental health needs while adding the treatment of substance use disorders (SUD), expanding housing interventions, and increasing the behavioral health workforce. It also enhances oversight, transparency, and accountability at the state and local levels Behavioral Health Services Act.

[32] W&I Code § 5963.02(c)(3)(A).

[33] Sourced from DHCS MCP Boilerplate Contract.

[34] Definition derived from “Patient Experience” definition from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, from the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS).

[35] Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, Office of the Secretary, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Access to Health Services - Healthy People 2030.

[36] World Health Organization. WHOQOL - Measuring Quality of Life. Division of Mental Health and Prevention of Substance Abuse. World Health Organization. March 2012.

[37] Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Social Connection.

[38] Derived from “Student Engagement” definition on The Glossary of Education Reform.

[39] Definition sourced from the National Institute of Mental Health. In relation, “suicide attempt” refers to the non-fatal, self-directed, potentially injurious behavior with intent to die as a result of behavior, and “suicidal ideation” refers to thinking about, considering, or planning suicide.

[40] DHCS does not have a formal definition for “suicide,” but acknowledges it as a complex public health challenge involving many biological, psychological, social, and cultural determinants. More on its program can be found in the DHCS Suicide Prevention Fact Sheet.

[41] Referenced from the California Department of Public Health.

[42] Referenced from the California Department of Public Health. Statistic is sourced from the California Overdose Surveillance Dashboard.

[43] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. About Criminal and Juvenile Justice.

[44] Ingrid A. Binswanger, Marc F. Stern, Richard A. Deyo, Patrick J. Heagerty, Allen Cheadle, Joann G. Elmore, and Thomas D. Koepsell. “Release from Prison — A High Risk of Death for Former Inmates.” New England Journal of Medicine, January 2007.